Einstein believed in the existence of a spiritual God based on what he called the ‘spirit manifest in the laws of the universe’ and a sincere belief in a ‘God who reveals himself in the harmony of all that exists’.

Einstein believed in the existence of a spiritual God based on what he called the ‘spirit manifest in the laws of the universe’ and a sincere belief in a ‘God who reveals himself in the harmony of all that exists’.

Einstein’s parents were ‘entirely irreligious.’ They did not keep kosher or attend synagogue, and his father, Hermann, referred to Jewish rituals as ‘ancient superstitions’.

Einstein was critical of, fanatical atheists similar to the slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains which they have thrown off after a hard struggle. They are creatures who in their grudge against traditional religion as the ‘opium of the masses’ cannot hear the music of the religious spheres.

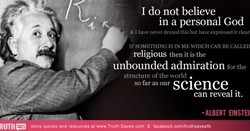

Einstein went on to say that there was one religious’ concept that science could not accept of a judgmental deity who could meddle at whim in the events of his creation. The main source of the present-day conflicts between the spheres of religion and science lies in this concept of a personal God. He saw no contradiction between science and religion.

As he put it, “The religious inclination lies in the dim consciousness that dwells in humans that all nature, including the humans in it, is in no way an accidental game, but a work of lawfulness that there is a fundamental cause of all existence.”

Did he believe in God?

“I am not an atheist. I don’t think I can call myself a pantheist to the doctrine that the universe, taken or conceived of as a whole is God. The problem involved is too vast for our limited minds. We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but doesn’t know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God. We see the universe marvelously arranged and obeying certain laws but only dimly understand these laws.”

When asked if he was religious, Einstein replied, “Yes. you can call it that. Try and penetrate with our limited means the secrets of nature and you will find that, behind all the discernible laws and connections, there remains something subtle, intangible, and inexplicable. Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion. To that extent, I am, in fact, religious.”

Do you believe in reincarnation, immortality?

“No. And one life is enough for me.”

Do you believe in free will?

“I am a determinist. I do not believe in free will. Jews believe in free will. They believe that man shapes his own life. I reject that doctrine. In that respect, I am not a Jew.”

Scientists aim to uncover the immutable laws that govern reality, and in doing so they must reject the notion that divine will, or for that matter human will, plays a role that would violate this cosmic causality.

His belief in causal determinism was incompatible with the concept of human free will. Jewish as well as Christian theologians have generally believed that people are responsible for their actions. They are even free to choose, as happens in the Bible, to disobey God’s commandments, despite the fact that this seems to conflict with a belief that God is all-knowing and all-powerful.

Einstein, on the other hand, believed that a person’s actions were just as determined as that of a billiard ball, planet, or star.

“Human beings in their thinking, feeling, and acting are not free but are as causally bound as the stars in their motions, everybody acts not only under external compulsion but also in accordance with their inner necessity, a man can do as he wills, but not will as he wills.”

But Einstein’s answer was to look upon free will as something useful, indeed necessary, for a civilized society, because it caused people to take responsibility for their actions.

“I am compelled to act as if free will existed,” he explained, “because if I wish to live in a civilized society I must act responsibly.”

He could even hold people responsible for their good or evil, since that was both a pragmatic and sensible approach to life, while still believing spiritually that everyone’s actions were predetermined.

“I know that philosophically a murderer is not responsible for his crime,” he said, “but I prefer not to take tea with him.”

The foundation of morality, he believed, was rising above the ‘merely personal’ to live in a way that benefited humanity. He dedicated himself to the cause of world peace and spoke out for racial justice. And he tried to live with humility, simplicity, and geniality even as he became one of the most famous faces on the planet.

For some people, miracles serve as evidence of God’s existence. For Einstein, it was the absence of miracles that reflected divine providence. The fact that the world was comprehensible, that it followed laws, was worthy of awe.